- The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) has launched a review of capital risk weights and adequacy.

- The review responds to concerns that the 2019 capital framework was seen in many quarters as overly conservative, potentially constraining credit supply and competition. The new framework aims to balance financial stability with efficiency and competitiveness, aligning New Zealand with peer jurisdictions rather than targeting a “1-in-200-year” stress scenario.

- At the same time the RBNZ have lowered the financial barrier to become a deposit taking institution (a “bank”) from $30mn to $5mn.

The proposals lower bank capital requirements but...

The proposals mark a shift away from conservatism toward greater efficiency, with a lower calibration of capital requirements. The RBNZ have provided two options for the market to provide feedback on. Our guess is that “Option 2” offers the best economic benefits, perhaps at the margin more bank-friendly and return on equity (ROE) positive, while still maintaining a credible safety net through total loss attributing capital (TLAC). However, as we discuss later, the success of implementing TLAC proposals funded from Australia is more than likely equally a matter for the Australian bank regulator.

For investors, the consultation suggests a mildly bullish outlook. It may slightly lower loan costs, it may nudge higher GDP growth, and the changes could also lift New Zealand bank profitability. Sounds good? Well, the modelling comes at the expense of a modest cost to financial stability.

The proposal has two elements. First, lower specific sector risk weights especially for banks that do not use their internal models, and second, lower overall capital requirements (than those outlined in the 2019 review).

What we like about the proposals is the detailed approach to applying risk weights to loans for the smaller banks on standardised models. Risk weights determine the quantum of risk assets against which banks need to hold capital. We particularly like the adjustment downward on the risk weights on loans to small and medium sized businesses. The more granular standardised risk weights reduce required capital by ~5% system-wide, with the largest relief for agriculture and SME lending. Again, the change in risk weights applies to the smaller banks; the larger banks remain at best at a floor of 85% of the capital requirement that would be required under the standardised models.

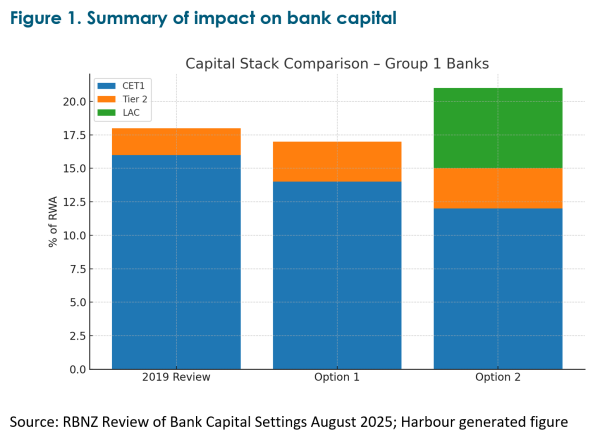

The shift in overall capital mix has two options. Option 1 relies on just dropping Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) requirements, while Option 2 substitutes a further lowering in CET1 with the addition of internal Loss-Absorbing Capacity (LAC) for the largest banks. While the RBNZ do not lay out a preference, it seems us that there are a number of nods towards Option 2.

For instance, the paper notes that compared with the 2019 capital review, total required capital falls by ~12% under Option 1; Option 2 cuts CET1 by ~10% but introduces 6% LAC, lowering funding costs while modestly lifting bank return on equity (ROE).

Of course, there is a ‘however’ to the Option 2, LAC proposal. Who provides the LAC capital, or, more specifically, who provides the crisis capital to the New Zealand bank? The RBNZ paper says that “our preferred crisis management approach for Group 1 deposit takers” (total assets of more than $100bn) is “an Australian-led “group” resolution approach, under which the Australian parent would transfer or downstream sufficient capital to the New Zealand subsidiary to restore its viability”. The paper calls this “internal LAC”. We will have to see the reaction of the Australian banks, and APRA (the Australian bank regulator) to this option as it implies a potential risk transfer to Australian shareholders. That perspective could kill Option 2 even it was the favoured option for the RBNZ.

It will take a little bit for this proposal to settle into a response from the banks, particularly the Group 1 banks, as it could well be the case that the enhancement of return on equity in the New Zealand businesses from lower risk weights and lower CET1 could be offset from the proposal to stand behind the subsidiaries with total loss absorbing capital. The RBNZ also discuss flexibility in crisis management with a range of fallback options including the separation of the New Zealand subsidiary from its parent.

Will the proposals impact lending rates?

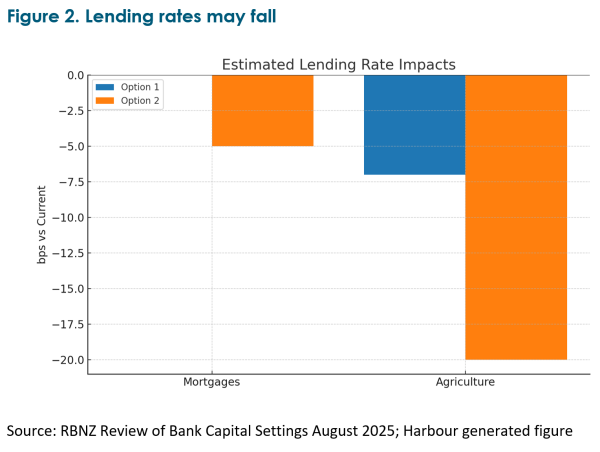

The RBNZ updated their model used back in the 2019 review. It remains highly sensitive to which option is chosen and the funding environment. The bank paper estimates lending rates may fall by -6 to -10 bps for Option 1 and by -11 to -17 bps for Option 2. With agricultural lending rates seeing the biggest benefit, perhaps up to 20bps lower.

We think this is a key factor in passing on broader advantages to the overall economy but is extraordinarily hard to estimate. The RBNZ estimates a potential lift to GDP growth of a modest 0.08% to 0.14%. Perhaps that misses the potential additional impact from more competition, and the reallocation effect of changing standardized risk weights.

Who really wins?

It seems that the proposals reflect on a trail of feedback since the original 2019 review of bank capital. The big question back then was whether the move to squash a 1 in a 200-year banking crisis was the right sort of risk appetite for consumers, businesses and the economy overall.

It’s hard to be specific but seems reasonable to reflect that the hurdle to lift competition in the banking sector is more restricted under current capital settings. The Oliver Wyman review embedded in the RBNZ proposal shows New Zealand currently heading towards the highest bank capital requirements. We think the proposal on standardized risk weights, CET1 capital, and Option 2 (the LAC bail-in from Group 1 banks) starts to balance the risk appetite.

Existing domestic Group 2 and 3 banks (the smaller deposit takers) will see lower capital requirements, potentially lifting competition. However, the more important signal is the lowering of the financial barrier to becoming a bank in New Zealand from $30mn to $5mn. That might not sound a substantive change, but we think that the opportunity now for digital challenger banks to look at the New Zealand market is much greater. The appearance of Level 4 Core Banking systems (for instance an institution akin to Macquarie Bank in Australia) to provide a significant competitive force, is likely the new element in this review that adds to potential efficiency – see our earlier Navigator, Technology, competition and risk are reshaping Australian banking.

We expect the real winner will be consumers and small businesses.

IMPORTANT NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER

This publication is provided for general information purposes only. The information provided is not intended to be financial advice. The information provided is given in good faith and has been prepared from sources believed to be accurate and complete as at the date of issue, but such information may be subject to change. Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made regarding future performance of the Funds. No person guarantees the performance of any funds managed by Harbour Asset Management Limited.

Harbour Asset Management Limited (Harbour) is the issuer of the Harbour Investment Funds. A copy of the Product Disclosure Statement is available at https://www.harbourasset.co.nz/our-funds/investor-documents/. Harbour is also the issuer of Hunter Investment Funds (Hunter). A copy of the relevant Product Disclosure Statement is available at https://hunterinvestments.co.nz/resources/. Please find our quarterly Fund updates, which contain returns and total fees during the previous year on those Harbour and Hunter websites. Harbour also manages wholesale unit trusts. To invest as a wholesale investor, investors must fit the criteria as set out in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013.